I’ve been thinking a lot about what it means to staunchly claw into your morals in a world that nudges you to loosen your grip on them at every turn.

A few months ago, I was offered an opportunity that a younger, or rather, older version of myself might’ve jumped at. It was an opportunity that, should I take it, positions me in close proximity to many of my longest standing personal aspirations. One that could bring me that much closer to achieving a scholarship for the master’s I can’t otherwise afford. One that would propel me skyward in my career – have people listen, have people notice the causes I fight for. And yet, there was a catch, as there so often is.

The Source of my opportunity is one that has been blatantly complicit in violence, suffering, in genocide - to put it lightly. And so, I turned it down. A decision that a younger, less informed, and more ambitious version of myself might’ve never understood, let alone forgive.

I don’t think I am exceptionally virtuous for turning it down. In fact, I am nearly always wracked with a guilt I can’t seem to squander. In the days leading up to my rejection of the offer - an unceremonious email to the Source - I had a series of conversations with those near and dear to me. but it was the stark disapproval from older people who have been in the same field I am a fledgling in, that stuck with me the most.

“You are too young and too inexperienced to be turning down opportunities as prestigious as this,” “it’s a wonderful thing that you are so driven by your morals, but you will soon learn that life doesn’t get any easier.” And the classic “I think you should take it. the best way to change the system is to get into its bloodstream,” ahh, but can the master’s tools dismantle the master’s house?

I don’t regret my decision. but I would be lying if I didn’t confess that I’ve wondered what it might feel like to set my morals, my beliefs, and values aside to take the opportunity. I flirted with the idea. Allowed myself to string up the most far-fetched justifications -- the same flimsy calibre of those that were told to me. I’d tell myself that the Source is not directly linked to the very violence I have taken to the streets to protest. That they have even condemned it! Is that not enough? Can’t I be selfish just this once?

No. No, I could not.

This was not the first time I’ve been confronted with the inconvenience of integrity. But it was a poignant reminder that your dreams may not always be compatible with your morals. That sometimes the cost of integrity is opportunity.

And I’m certain I’m not the only one.

The snarky comments and eyerolls received by people who don’t see the sense in an enduring commitment to boycott, the friends we have lost and connections we have severed, the patronising smiles and secret looks shared by people who find your rage, your grief, your empathy both, inconvenient and confronting.

But that inconvenience is never more pronounced than when you too find yourself at a crossroads between principle and possibility. Living in South Asia - the ‘developing world,’ so to speak - I am no stranger to how difficult it is to come by Opportunity. I was asked why I wouldn't take an opportunity that is guaranteed to help my family, my community and support the development work I pour my heart and soul into every day.

But what is support, funding, and recognition if I am expected to replace my integrity with complicity? What is development if it is intertwined in the very institutions that bankroll apartheid, profit off the championing of one cause while actively silencing another? Another lap around the system to reinstate that yes, it is in fact, a vicious cycle.

But here’s what I’ve learnt: so much of our allegiance to the resistance is rooted in our ability to resist. Even and especially when it’s not easy.

To take it to a place of White Lotus

The last episode of The White Lotus stood out to me, perhaps more so than any other episode this season.1 Maybe that’s because we finally see the quieter, more latent themes emerge out of the shadows cast by the more glaring ones that coloured this season.

To be more specific, it was the culmination of Gaitok (Tayme Thapthimthong) and Belinda’s (Natasha Rothwell) individual storylines that I found most thought-provoking and felt were, in many ways, scathingly familiar.

I told a friend the day before the finale aired that I’ll be alright so long as Gaitok, Belinda and Chelsea (Aimee Lou Wood) emerge unscathed.2 I couldn’t have predicted that the Gaitok and Belinda we witness throughout the course of the final episode are so astoundingly different to the Gaitok and Belinda we came to know and love all season.

I welcomed Gaitok’s sensitivity that bordered on an almost nail-biting naïveté, constantly making me want to shake him by the shoulders. It was a flavour of masculinity that we don’t often see on this show. At least not in the absence of something bizarrely freaky.3 It is also version of masculinity that is rooted in a seemingly profound sense of self -- one that doesn’t insist on itself. There is an unwavering resoluteness between him and the morals he holds close. His discomfort with the gun and the peripheral threat of violence his job entails, as well as his refusal to bend to the whims and fancies of his other male counterparts had me rooting for him. I think we all were.

His commitment to the Buddhist principles of non-violence set a certain tone for his storyline.

In a pivotal scene between Gaitok and his love interest, Mook (Lalisa Manoban), he confesses: “Pee Lek thinks I don’t have the killer instinct. Maybe he’s right. Buddha condemns violence.” To which Mook responds: “It’s good you have strong morals. But you have to live in this world.”

In the final shootout scene, I truly believed that Gaitok would once again choose his morals, instead of the vaunted promotion from security guard to bodyguard that is alluded to all season. And for a split second, the anguish written across his face as he made the shot almost had me thinking that he might shoot himself too. But alas, in a prologue-esque montage we see a Gaitok clad in black, sitting in the driver’s seat of none other than the resort owner, Sritala’s car. Buddhist values: 0, promotion: 1

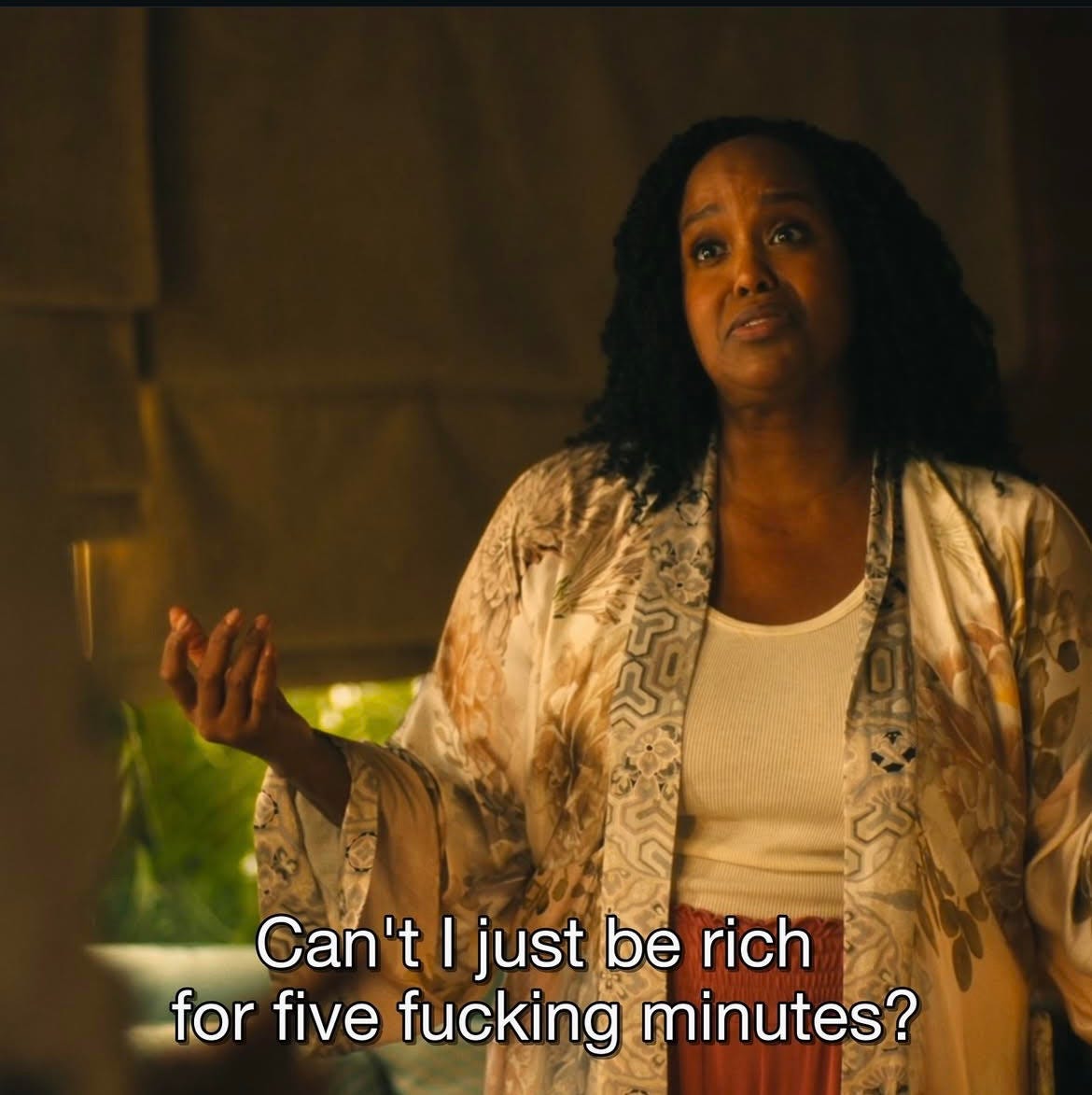

And then we have Belinda, who parallel to Gaitok, holds yet another mirror up to the audience asking: to what extent are you willing to sacrifice your morals in order to achieve a material dream?

We first meet Belinda in season 1, where she manages the spa at the The White Lotus resort in Maui, propelled by bigger aspirations to open her own wellness centre. Seeing promise in Belinda, a certain Tanya McQuoid makes the generous offer to fund the goal, only to rescind the offer at the 11th hour and leave Belinda jilted at the altar of her dream.

And so, in season 3, there is a subdued, more cautious energy that shrouds Belinda – an unease, perhaps even insecurity. She’s hardened by the reality of a seemingly severed dream, and here she is, on something resembling an exchange program, resigned to the disappointment of succumbing to The White Lotus 9-5.

Enter smarmy Greg/Gary (Jon Gries) - Tanya’s former lover and alleged executioner, with none other than a suitcase full of hush money to bribe Belinda (who apparently moonlights as a private investigator) into silence over Tanya’s mysterious death.

We root for Belinda in her vehement rejection of the $100,000 — “its blood money!” she declares with a shaky finality, more than once. We root for her in her dalliance with the kind, gentle Pornchai, who, we are led to believe may be a potential business partner to Belinda. In the soft afterglow of Pornchai’s quiet belief in her, she finds herself cautiously back at the drawing board, once again working towards a deferred dream.

And still, the blood money looms. An obstacle and distraction as much as it is an alluring possibility. So, when at last Belinda crumbles at her son’s prodding, she walks away with not the initially agreed upon $100,000 but five million dollars to her name. It’s a moment that feels both, triumphant and tragic. Here’s a woman who we have come to know to almost routinely choose dignity over convenience…this time choosing exorbitant convenience.

I felt incredibly at odds about the conclusion of Belinda’s storyline. In a post finale debrief, a friend says to me “Belinda’s been through hell, she deserves that money!” and I am compelled to agree. With that money she will not only establish her own wellness centre but ensure its guaranteed success. A triumph on all counts, yes?

And yet there is something so deeply unsettling that prevents us from wholeheartedly cheering for Belinda. The dream is finally within reach, but it comes at the cost of her integrity, a core tenet of Belinda’s character that sets her apart from the rest. It also comes at the cost of her relationship with Pornchai, leaving him in the rear view mirror as collateral damage – an all too eerie mirroring of exactly what was done to her by Tanya in season 1. It is this very dissonance: we want to cheer for Belinda, and in many ways we do. But we’re forced to reckon with the uncomfortable reality that liberation, when negotiated through a system entrenched in exploitation, rarely comes untainted. Is meaningful progress truly possible in a system that is otherwise designed to fail us?

Belinda and Gaitok’s choices to take the money and rise to the promotion are also not framed as a descent into villainy, but rather a commentary on the inconvenience of morality, the luxury of integrity. And perhaps this is the genius that propels the success of this series. Mike White’s ability to not just write nuanced characters but to place them in a world that feels far too familiar to be fictional, far too relatable for it to not hold up a mirror to our current reality.

So much about this theme felt salient to me.

The cataclysmic violence that we have borne witness to or endured in siloes, has in recent years asserted itself as a shared collective reality. From genocide, political and structural violence, climate change, fascism, to extractive, exploitative capitalism – the list doesn’t end even if we do. And as movements have erupted across the world protesting these mass injustices and violence, there has also emerged a collective political invigoration, one catalysed by a shared radicalisation born from grief, rage, and the urgent demand for change.

But resistance in this current political climate, has taken on a layered definition. To take meaningful political action, to participate in the resistance, also necessitates a quieter, more personal form of resistance - the resistance of comfort, luxury, and of course, convenience. Propelled by a sharpened moral compass, we’ve downloaded apps to help us identify which products at the grocery store funnel our money to aid genocide(s), we think twice before we fall for the luxurious allure of the latest iPhone, or the seemingly endless convenience of AI and all its possibilities. We interrogate the sources of our funding, our scholarships, project grants, and donations. We question our association with the structures that have thus far enabled some of us to live comfortably. The very structures that lull us into a languorous comfort, while perpetrating a far greater violence elsewhere.

The resistance has revealed to us that participating doesn’t only consist of grand, sweeping acts of political dissent, but also everyday micro decisions. It has revealed to us that the fight for collective liberation is oftentimes inconvenient, uncomfortable, and disruptive. Probing us to sacrifice our creature comforts, our material allegiances to brands, aesthetics, luxury and even people. To take the long way. The harrowing images we bear witness to every single day, of martyred babies, men and women sacrificing their lives for their homelands, of wildfires and floods and hurricanes wiping out cities, of suffering and grief and destruction, has made it impossible to ever put our moral blinders on ever again.

And while our fervent clawing into these moral positions and personal values are largely rooted in place, The White Lotus does a phenomenal job at highlighting the inconvenience of this consciousness, flipping the script and asking the viewer: what would you do when your morals and your aspirations don’t complement one another? What would you do if your moral compass, painstakingly cultivated and preserved, starts to impede on your own personal development and upward mobility? What do you do when it starts to feel like an obstacle to your own survival?

This moral conundrum being conveyed through Belinda and Gaitok – two people of colour trying to make it, in a line of work that favours a certain type of person – outstandingly reveals this aspect of survival.

Piper Ratliff (Sarah Catherine Hook) for instance, abandoning her whole spiritual enlightenment schtick after having spent a night in a monastery, did achieve a certain shock factor – after cringing at her family’s sumptuous and extraordinarily out of touch leanings all season, her decision to discard the journey in favour of embracing her wealth and privilege seemingly in one fell swoop, did cause some whiplash. And yet in hindsight, was wholly unsurprising.

With the ever-decorative white woman tears streaming down her face, she tells her family “there’s so much suffering in the world, and, like, we have it so easy and other people have it so hard. I just..I feel like it's really unfair,” to which her mother (Parker Posey) replies: “Nobody in the history of the world has had it better than we have. Not even the old kings and queens. The least we can do is enjoy it…If we don't, its offensive.”

The idea that not enjoying your obscene wealth being somehow offensive, is a blatant caricature of neoliberal hedonism, bordering on satirical until you remember that this is, in fact, how a great many people rationalise injustice.

Piper and by extension the Ratliff family, stand in sharp opposition to Gaitok and Belinda. Piper’s suffering is elective, theoretical, and momentary. Her morality is not a burden nor an inconvenience but an accessory. Gaitok and Belinda however, contrast this. They tell a story about the inconvenience of integrity, the burden of morality. In a world designed to fail them, they are offered a golden ticket – a choice.

And it is in that choice, the decision between the individual or the collective, the self or the right thing, that the The White Lotus, offers its most cutting critique. It doesn’t let anyone, not even its most principled characters, off the hook. It doesn’t romanticise sacrifice, nor does it necessarily demonise ambition. Instead, it situates itself squarely in the grey, holding a mirror up to us all.

This tightrope between survival and selfhood, glory and sacrifice, in whatever angle you look at it, is something I’ve not been able to stop thinking about. I have thought a lot about the uncertainty, disruption and, the inconvenience we thrust ourselves into when we allow ourselves to be moved by the collective, to feel even a fraction of the grief and suffering that gnaws at the edges of general complacency. The inability to look away.

In many ways, I am grateful for the pain, the outrage, and the grief I have felt. To know how my actions, as little or large as they may be, can either hurt the movement, or propel it. I am grateful for the conundrum because therein lies the evidence of a persevering humanity - one that extends itself beyond material gain, luxury, and the easy way out.

And as the world continues to ask us to loosen our grip, to numb ourselves, to take the money and shoot the shot. To rise up the ranks no matter the cost, to surrender to the seemingly ‘little’ conveniences afforded to us in a fast paced world and luxuriate in the riches and never question how they came to be – the smaller revolutions lie in asking the inconvenient questions. To have the gall to ask: at what cost?

And the cognizant understanding that the power, the story, the glory no longer lie in where we are going, but how we get there.

if you like my work and would like to support me, you can do so by buying me a coffee :)

season 1 will always gag !!!!

can’t have everything now can you

Lochlan Ratliff I’m looking at you

dru this is SO GOOD!! firstly, so proud of u for standing on business and committing to your morals and values, not too many people can say the same, for precisely the reasons you highlighted in this essay! you named something that is incredibly prevalent in society but rarely identified beyond a surface level, and you did it with exquisite writing that captivated me as always! skin deep resistance is so entrancing to so many because it doesn’t require the hard work and sacrifices that true resistance asks for. thank you for your words and A++ white lotus reflection!!

Congrats on standing in your integrity! While I agree with the older people you spoke to who said, “life gets harder,” perhaps if you’d have spoken with people more like you, who had also made life choices based in their morals & ethics they would tell you the same: life does get harder, but as you age you also notice a difference between those who have lived by their integrity and those who have sold it along the way. You can’t buy it back. You can’t rewrite your own story to make yourself sound better. When you choose to live from your heart & integrity life actually becomes richer. You can lean on your choices as you go, not try to hide them in case someone finds them, because they do define you from the inside out. Those are foundations money can’t buy. You’re good. Stay true, Dru! 💫